|

|

Kansas Limestone

H I S

T O R Y

|

Fence Posts |

| |

|

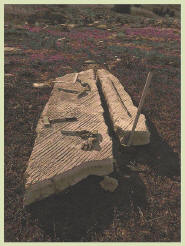

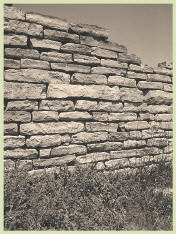

“Land of the Post Rock” is a distinction given to about 3 million

acres in North Central Kansas- an area where a single bed of rock (the

8-12” Fencepost bed of the Greenhorn limestone layer) was used so

extensively for fence posts during early Kansas settlement days that

the posts have become an identifying feature of the landscape.

Settlers to Kansas found that the area was destitute of timber and

turned to the material at hand…a layer of rock close to the surface

that they soon found could be used for fencing as well as building.

Besides being durable and fire resistant, this limestone had several

other advantages. Being close to the surface it could be obtained

easily with the proper tools and techniques. It was uniform in

thickness (8-12”). It was persistent, extending with little

interruption for miles. And when freshly quarried it was soft enough

to shape with tools and hardened after being exposed to air.

There

were of course disadvantages. Quarrying rock in “post” length required

skill, hard work, and time. Once split out and shaped they had to be

transported. This again required hard work and ingenuity as each 5 to

6 ft long post weighed about 350-400 lbs.

Posts

were hauled/delivered to the pasture using various means. To go short

distances a “sled” or “boat” was often used. This has been described

as being a large forked tree limb with branches laid crosswise to make

a platform which would hold several posts. A team of horses would then

pull the sled to the post hole.

After

being delivered to the fence line it was considered a simple job to

tip the post (always the heavier end) into the prepared holes. The

holes were dug by hand to a depth of 18” to two or more feet

(depending on the height of the posts). Holes were dug about every 15

feet so that in the finished fence line there were about 320 posts per

mile. Corner posts were propped to stay in a vertical position by

leaning other posts against them at about a 45 degree angle (generally

in the direction of the fence lines).

|

|

Building Stone |

| |

|

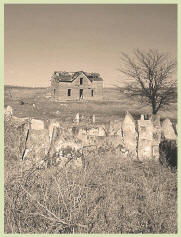

Often because of its name and unique use, Fencepost Limestone is

identified with stone posts- neglecting its primary use as building

stone. Even settlers with little knowledge of how to quarry or lay

stone used it to line wells and cellars, to form inside walls and

outside fronts of dugouts, to build fireplaces, to make steps and

porches…

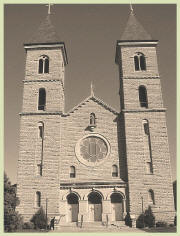

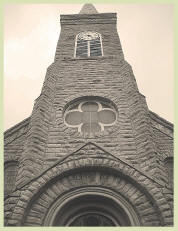

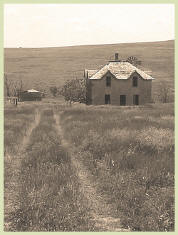

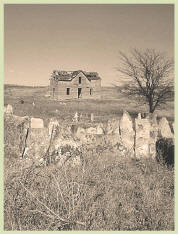

The

1870’s was Post Rock Country’s formative period as well as being the

period of time that saw the greatest influx of European

immigrants…Bohemians/Czech, Volga Germans, Germans, Swedes, Danes,

Norwegians, Scots, and English. Soon every community in North Central

Kansas included stone masons from the “old country” which assured

knowledge about the building potential of post rock and their

inclination to use it. The emerging (and now remaining) architecture

was the most visible link of these groups/communities to their past

and gives insight into the way they worked, played, and worshipped.

Many agree that of all influences in central Kansas none exceeded that

of the Germans. Despite grasshoppers, crop failures, and other

adversaries, most Germans held on.

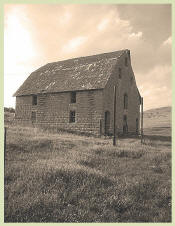

Cooperative work involving building with stone gave those with little

or no experience a chance to learn from a trained craftsman. By the

1880’s improvements on homestead claims included stone houses,

outbuildings, foundations and footings, wells, walls, feeding/watering

troughs, fence posts, gate posts, hitching posts, clothes lines, and

sidewalks.

|

|

From the quarry...

to setting the stone

(tools, quarry process, dressing, lime mortar) |

Tools

used in the quarrying and shaping process were simple. They included

feathers and wedges (plugs), stone drills and bits of various sizes,

chisels, stone hammers, slips and scrapers, and scribers. Most of the

tools were made at home forges or in local blacksmith shops.

The

quarrying process for obtaining building block, fence posts, or other

products was the same: holes were drilled about 4 or 5” deep into the rock

and 9- 12” apart along a line marked for splitting; feathers and wedges

were placed in the holes; and tapping the wedges lightly with a stone

hammer split out the slabs, posts, or blocks.

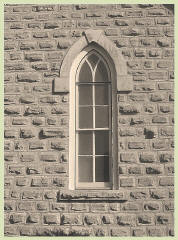

Although

building block size was standard (2’x8”x8”), there were a variety of ways

in which a block was dressed or finished: rough quarry faced, axe

flattened (characterized by the kerf marks of the axe), pitched faced

(also know as pillow faced), and sawn (although traditionally done with a

two man bucksaw, some ingenious settlers came up with alternatives such as

a mechanical saw on a beveled gear driven by a mule walking in a circle).

Special hammers and chisels were used for finely dressing or

architecturally carving lintels and sills (and sometimes quoins). Lintels

were unique from building to building and were an opportunity to add an

element of style and artistic beauty to a structure. Sills often followed

in the style of the lintels and were usually weatherized to help shed

water.

The

mortar needed to lay building blocks came from “slaked” lime…burning

broken pieces of limestone in crude kilns along creek banks to extract

(which produced) a lime powder used for mortar and plaster. One needed to

begin “slaking” their lime long before any other element of the building

process could begin. Burning lime mortar and plaster was one of the first

industries to evolve with limestone quarrying and the building trade.

|

Sidewalks, Bridges &

Caves |

Sidewalks were the pride of many post rock towns, historically quoted as

being the “best sidewalk in Kansas”, and “firm under feet for

generations”. The large pieces were hauled from local quarries fastened

with chains to the running gears of the rock wagon. Sidewalks could be

either a full 8” thick or a thinner flagstone. The flagstone came from

specific areas of Post Rock country (Mitchell and Lincoln counties) where

the Fencepost layer has a natural tendency to split along the center brown

streak, which made flagging from a slab of rock possible. This was used

extensively for sidewalks.

After

1900 when the building and maintaining of roads became important to the

region, post rock was called upon as a material for bridges. In building

bridges for both public roads and railroads, the stone arch emerged as a

popular architectural form. Native limestone bridges tended to be at least

twice the cost of any other type of bridge. Most thought the cost was

justified as the bridge would stand for hundreds of years and cost little

or nothing for repairs. In addition to this, nearly the whole amount paid

for a bridge was going back into the local economy (material/stone and

labor).

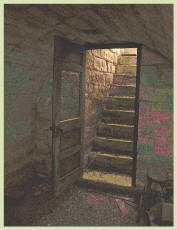

Another

unique use of the post rock was for stone arch caves, which farmers needed

for shelter from storms/tornadoes and a storage place for farm products.

The typical method for building caves was to lay stone blocks for the base

of the cave walls to a height of about a foot. Wood forms for the arch

were set on the wall bases and boards placed over the forms made a solid

arch. Stone blocks were then laid over those boards. When laying the

blocks was completed, the wood forms were knocked out. The stone arch (the

cave wall) would stay. Mortar was not necessary as pressure from the stone

would hold the arch in shape.

|

Post Rock's Decline &

1930's WPA |

|

|

|

By

1920 building with stone and regional development had passed their

climax. Among many factors contributing to this decline was the

availability of cheaper, easier to use building materials. Many of the

old stonemasons were leaving the scene and young men (returning from

WWI) took work away from the homestead. A new type of economy and pace

of life was evolving. Power machinery began to arrive on farms. The

automobile gave residents mobility and the area accessibility.

Homesteads were losing their self-sufficiency status. Rural farming

began shifting to fewer farms.

The

depression of the 1930’s made possible a brief comeback of post rock

as a major building material. It was widely used in public

construction projects funded by the federal Works Projects

Administration (WPA). No posts were quarried or set under the WPA, but

post rock was used in many building projects: schools, libraries, city

halls, community buildings, bridges, park shelters, recreational

facilities, and courthouses. Post rock was again a resource that came

to the aid of its regional economy, leaving behind a multitude of

incredible limestone structures and adding to the legacy …”Land of the

Post Rock”. |

|